October 1, 2009

By Mike Hudspeth

We’ve all heard the mantra, “form follows function.” In a nutshell it means that what something does will dictate how it looks. And while many of you are nodding in full agreement that the functional requirements of a device will often shape what it looks like, that’s not the only way to look at things.

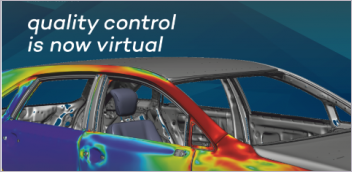

Figure 1: By laying out every part of your user experience you not only have a better idea of how your product will be used, but you might see problems you might not have seen otherwise. |

In a perfectly engineered world everything would be either right or wrong—it would make sense or it wouldn’t. But we live in a world where there are as many points of view as there are people, and that makes things somewhat more complicated—especially when designing the “next great thing.” So while engineers are trained to design things that work, engineering school usually skips the bit about designing things that people want. It’s not an objective, numbers-based exercise. Instead, it involves emotion and personal taste and ventures into that overlooked corner of industrial design.

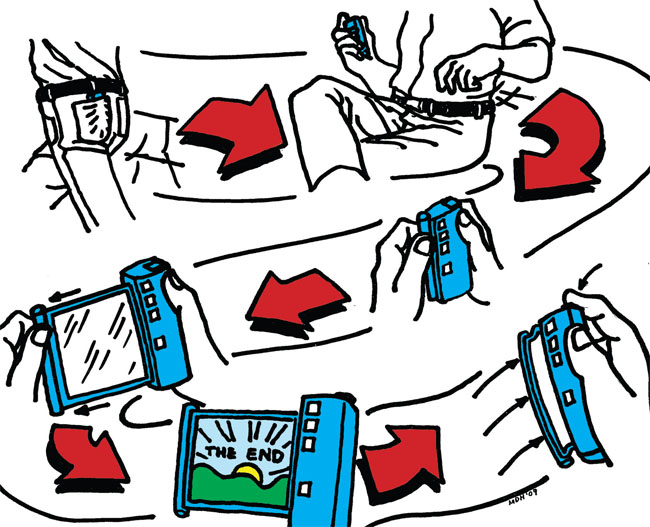

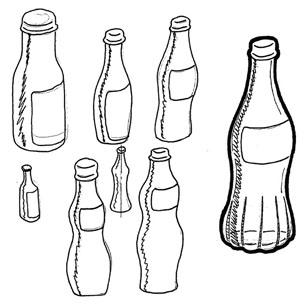

Figure 2: Imagine what the world would be like if we hadn’t been gifted with the gene for exploring. By drawing out and looking at a variety of designs you can explore the shape or function of your product. When the time comes to make a choice about which way to go, having choices makes all the difference. |

That creative spark

There are many ways to quantify a winning design. From measuring the profits it brings a company to determining how it fulfills customer expectations and from generating repeat business to fitting a sustainable and responsible mission, perhaps a winning design is one that does all these things, and more. All it has to do is be all things to all customers.

To be sure, industrial design (ID) is about styling, but it goes further than that. An industrial designer’s job encompasses a wide range of important functions—all of which add value to the enterprise. Industrial design is also about taking the best of each discipline involved in the development of a product—from manufacturing to marketing—and combining them in a way that best meets the product’s needs. To say industrial design is all about art is to put the profession into a very small box. Of course, to say engineering is all about the numbers does the same thing. But when we are under so much pressure to think outside of that box, we must cultivate innovation just to survive and industrial design is ultimately about innovation.

The Methodology Of Industrial Design

When I saw The Empire Strikes Back for the first time, I honestly thought Yoda told Luke, “always emotion is the future.” I was later corrected that he actually said “in motion,” but the damage was done and I’ve since believed that emotion rules mankind. Look back through history. Wars have been fought because of it. Grand epics have been written to stir it. Great acts have been accomplished in the pursuit of it.

People like things for intangible reasons, emotional beings that we are. We need and desire. We look at the world through emotional eyes. So to sell to humans you have to understand them—and their emotions. What is it about a product that will elicit emotion? It can be different in each culture, yet a designer must know what each design feature will say to a customer and so designs for emotion.

The next thing an industrial designer must do is model the experience. From an ID perspective, you don’t just create a thing—you design an experience. The product will be used and a designer must think through each step in that experience and consider what the user is going to see. A storyboard is very useful for this. This collection of fast sketches depicting each part of the user experience (see Figure 1) looks at the range of motion, the dents and dings, and the conditions the product will likely be subjected to. The more steps you can get into the storyboard, the more accurate your design will be.

|

Sketch, Sketch, Sketch!

If variety is the spice of life, then iteration is the life blood of good design (see Figure 2). Draw your product. Document each and every thought or direction you can. You don’t have to be Leonardo DaVinci, just get the concept down. No one can consider an option they haven’t seen. It’s usually good to place a time limit on this. Once you’ve got all your sketches finished, go through them and select several that strike your fancy—say, six. Then you present those to the rest of the team. The team will narrow them to three that can be mocked up and presented to the customer.

While the traditional way to sketch a concept is with pencil and paper, there are many newer tools that can be used to great effect. Try a digitizer tablet or tablet PC. Wacom has its Cintiq line of touchscreen monitors that are fun to work with. There are many good software programs as well. A few that come to mind are Alias (the defacto standard for industrial design) and Sketchbook Pro from Autodesk, Corel Painter, CorelDRAW!, Adobe Illustrator, and Adobe’s Photoshop. All of these products will help. Of course, once you’ve sketched your concepts and selected which ones to develop, you’re going to need to model them using Alias, SolidWorks, Rhinoceros from McNeel North America, NX from Siemens PLM, Think3, solidThinking, or one of many others. Which tools you use really depends on your budget, your comfort level and expertise with the tools, and what your customer wants. (Many manufacturers will require results in a specific program.)

Along with what a product looks like, the industrial designer must also consider how it functions and how a user might interact with it.

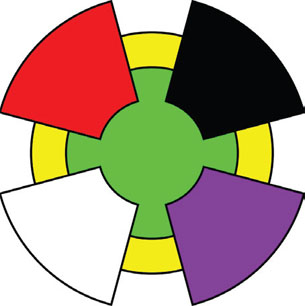

Psychology of Color Colors have emotional and psychological meaning. The same color can mean many things—even in the same culture. Color can elicit a strong emotional response—either good or bad. Below are a short collection of colors and their more common meanings: |

That interaction takes into account the product’s ergonomics—a much-thrown-about term these days. People generally think of ergonomics the same way they do styling, but it’s much more. Ergs are a measure of energy use. And economics is a study of resource use. Therefore ergonomics is literally about how much energy a product or system takes to use. How something operates is every bit as important as whether it operates. It’s an ease-of-use issue as well as a fit issue. If a product takes too much effort to operate, people won’t want to use it. Likewise, if one product choice has sharp edges that hurt, people will almost always buy the one that is soft or rounded.

Beyond the user, however, a good industrial designer will also keep the manufacturer in mind. Industrial designers must be familiar with all of the processes by which their designs will be produced. And since ease of manufacture and assembly can affect the final price of the product, it’s important for an industrial designer to keep price as a consideration. If you design in a lot of manual operations, the manufacturer will have to pay someone to complete them and pass that cost on to the customer.

Color is another very important aspect of a design. A product’s color palette can say a lot about the product. Color is not merely a function of the frequency of light that is reflected off a surface, but can excite an emotional response (see Figure 4). For example, why is red the color on the STOP sign? Consider that all creatures capable of seeing in color know red is the color of blood. Therefore, when they see something red, there is an emotional response that signals DANGER! In some cultures, black is the color of death, but in others it would be white (see “Psychology of Color”). The colors you use will elicit certain responses and convey specific feelings about your product and your company so approach color choice carefully.

The Many Facets of ID

There are many other facets of industrial design. Texture, shape, and a product’s impact on the environment throughout its lifecycle are just a few. A good industrial designer will consider how the product is made, used, and disposed of.

Industrial designers take all of these things into account when they create a concept. Despite what some seem to think, industrial design is not just about seeing how artsy a product can be made. Industrial design is about meeting the needs of the product in the most economical and responsible way. Industrial designers aren’t cheap, but they add significant value to the bottom line.

More Info:

Adobe

Industrial Design Society of America

Mike Hudspeth, IDSA, is an industrial designer, illustrator, and author who has been using a wide range of CAD and design products for more than 20 years. He is DE’s expert in ID, design, rapid prototyping, and surfacing and solid modeling. Send him an e-mail about this article to de-editors@digitaleng.news.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!