Making and Breaking Things for Fun

Makers and YouTubers blend engineering, entertainment and creativity.

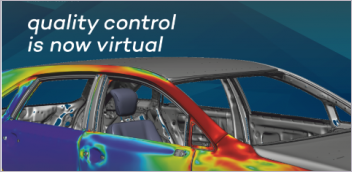

Ben Eadie, prop master on the set of “Ghostbusters: Afterlife” (2021), examines the iconic remote cars with ghost traps. Eadie is a long-time SOLIDWORKS and Onshape CAD user. Image courtesy of Ben Eadie.

Pre-processing and Meshing News

Pre-processing and Meshing Resources

Autodesk

Dassault Systemes

PTC

Latest News

November 1, 2024

If there’s something strange in the neighborhood, who you “gonna call?”—Ghostbusters. But … if the Ghostbusters need new equipment, they call Ben Eadie, also known as Dread Maker Roberts on YouTube.

In 2020, the production crew of “Ghostbusters: Afterlife” came to Calgary, Alberta, Canada—not your typical location for sci-fi films, but it happens to be Eadie’s hometown. Eadie has IMDB credits dating back to 2016, from “Star Trek Beyond” (2016, special effects assistant) to “Prey” (2018, special effects technician).

He’s also a long-time SOLIDWORKS and Onshape CAD user, with the skills to design props that are not only eye-catching but also functional. So the production team brought him on as the prop master.

“The remote-controlled vehicles, the remote ghost traps, the proton packs … They have to have blinking lights, and have to do certain things at certain times. So I was put in charge of them,” he recalls.

Ben Eadie: The Ghostbusters’ Prop Master

Eadie and his team designed and built some props themselves, but most were outsourced to trusted prop houses in Los Angeles—a standard practice in the film industry. As prop master, he also oversaw the production process.

“Usually prop houses and special effects teams might use programs like Blender or Rhino, but not a parametric CAD program,” Eadie remarks. “On the other hand, I can build the props in CAD and identify 80% of the potential manufacturing issues before making them.”

Eadie has worked with napkin drawings and what he calls “non-parametric blobs.” Sometimes he worked from a one-line description—“a Wilson volleyball that’s robotic.” It was for the actor Tom Hanks’ ceremonial first pitch to Larry Doby Jr., as the opening act of the Cleveland Guardians’ game against the San Francisco Giants at the start of the 2022 baseball season. On the day of the game, Wilson, remotely controlled by someone else, would make a number of attempts to run away from Tom Hank and refused to comply with the actor’s verbal commands, much to the amusement of those at the game. To make that possible, Eadie consulted with an acquaintance who designed the spherical BB-8 robot from the “Star Wars” films.

The job wasn’t as simple as Eadie first thought. He had to design his Wilson to be slightly bigger than a real volleyball to accommodate a sizable motor that he needed to fit inside. The change of scale in design was easily done in Onshape CAD software. For the final touch, Eadie himself stained his hand to add the palm print that was so much a part of Wilson’s expressions.

“I love working with directors who give me a detailed drawing or description of what they want—those who know what the object should look like and what it needs to do,” Eadie says. “The ones I worry about are those that came to me with ‘I want a plasma gun,’ because I usually end up spending a lot of time making changes later.”

Between Meshes and Parametric Geometry

When Eadie receives 3D files, they are usually exported from visualization programs like Blender or Rhino. In most cases, Eadie would design the concept in parametric 3D CAD. Today, his go-to CAD software is the browser-based Onshape from PTC.

Most CAD users in engineering and manufacturing might be stumped when asked to produce organic shapes with complex surfaces commonly needed in film work, but not Eadie. His CAD skills are beyond average. He once designed a Bugatti Veyron in SOLIDWORKS to test the surfacing features available in the software.

With directors he has previously worked with, the established trust allows Eadie to work from home and deliver the prop by the deadline. But when he needs to work on the set, he usually brings his iPad or iPhone.

“This is also another reason I like Onshape. It doesn’t matter what hardware I use because it’s browser-based,” he says.

Eadie sometimes uses augmented reality to superimpose the 3D model of the prop onto the actual set where it will be used. “I can ask the director for the camera angle and show him/her exactly how it will look on the set,” he explains.

Just because he’s making things for movies doesn’t mean he can ignore the rules of physics. With some giant contraptions for stunt work, Eadie is painfully aware of the risk of injury involved.

“I’ve made a car cannon that shot a car 40 feet into the air, and the car needed to roll on its side a certain way when it landed,” he recalls. “I always use FEA [finite element analysis] to see if there are weak spots. The best compliment to me is when the stunt team says, ‘This looks super-dangerous. You need to get Ben involved.’ It’s also highly stressful to work on those because a lot of things can go wrong.”

Eadie also has discovered that veteran prop makers and special effects technicians sometimes design structures that may look counterintuitive, but they have empirical knowledge and wisdom developed through trial and error over time; therefore, they generally know what they’re doing. “Sometimes I looked at what they had on the set and wondered, ‘Is it going to work?’ But then when I built a 3D model and verified it, I found out it would do what it needed to. It was very humbling,” he says.

Xyla Foxlin: Blending Art and Engineering

Xyla Foxlin graduated with an engineering degree from Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH), but found her calling as a YouTuber instead. With 449K subscribers currently, she is a Silver-circle YouTube creator.

“I’m a bit of a speedy jet with a broken compass, I’m always racing in the direction of the skill that’s caught my interest ... for now. My goal is to inspire others to get out to their local makerspace or their garage and get making things,” she reveals in her channel’s introduction.

On her YouTube channel, Foxlin has built a ukulele in 24 hours, a camper from scratch in 3 weeks, and sewn a form-fitting real-life costume that replicates the Specter Slayer skin in the PUBG Mobile shooter game. Her episode on creating a Mobius-strip violin was sponsored by Autodesk, which produced the integrated CAD-CAM-CAE software Autodesk Fusion she has been using. The software is also free for noncommercial, personal use.

“For a project like this, CAD is imperative. An accurate 3D model is necessary for my robot employees to cut from,” says Foxlin. (This is how she refers to her computer-aided machining or CAM system.)

“Fusion has CAM built in, so I can program my toolpath directly on my model without leaving the software,” Foxlin says. “I have all of my tools and feeds and speeds saved, which makes creating new models easy.”

At one point, Foxlin was stumped by the complex CAM operations involved, so Autodesk connected her to Wayne Griffenberg, Autodesk senior technical sales specialist. “Wayne really helped me think about CAD and CAM differently and more efficiently. A lot of it was simply a confidence issue, and being able to go through things with a patient and experienced mentor made hitting ‘Go’ on the machine an easier step to overcome,” recalls Foxlin.

“I love the way Xyla integrated the Mobius into her violin! During our first meeting, she was concerned about her initial method for cutting the Mobius Rib on the CNC router,” says Griffenberg. “We talked about simplifying the CAD/CAM setup by using parametric stock to account for variability and ‘smart fixturing’ to make cutting both sides easier. With this new approach, Xyla felt much more confident, and she executed it brilliantly.”

Since Foxlin is not a professional luthier, she also consulted with the veterans at Robert Cauer Violins in Los Angeles, CA. “They were not judgmental about my stupid mistakes, but they gave me some friendly ribbings on the dumb things I did. Within 30 seconds of looking at my violin, Robert could tell, ‘Your nut is in the wrong place, your fingerboard is going to buzz, and your pegs won’t fit …,’” she recalls. She also learned one iron rule from the master: don’t ever put on a violin nut using epoxy.

The final piece Foxlin needed to create was the bridge. “I’m always for do-it-yourself [DIY] but I’m not going to lie. If you’re building a violin, just take the bridge into a violin shop. It’s an artform and really affects the way the violin sounds,” she says. To test her finished DIY violin, Foxlin was joined by Mia Asano, an electric violinist on TikTok with more than 2M followers.

More Autodesk Coverage

More Dassault Systemes Coverage

More PTC Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at kennethwong@digitaleng.news or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE