Latest News

September 30, 2011

Bill Barnes, Lattice Technology‘s general manager, described himself as “an old CAD guy.”

With a chuckle, he said, “I’ve been in this industry way too long.” How long, you ask? “I go way back to mainframe CAD days,” he’d explain.

Having studied mechanical engineering at Portsmouth Polytechnic in the UK, Barnes began his CAD career at Autodesk as a product manager. In the past 25 years, he’s also held posts at Actify and Stereographics. At Lattice, his latest vocational home, Barnes is responsible for shepherding a suite of software. The company specializes in technologies that let you redistribute 2D and 3D design data to the extended manufacturing enterprise—those who need to read, review, and understand design data but don’t necessarily want to learn and operate a CAD system.

Good News-Bad News

“The good news is, everybody is coming into this market; the bad news is, everybody is coming into this market,” Barnes quipped.

The field is quickly getting crowded (some might say “overcrowded”), with nearly every major CAD vendor releasing its own software to republish CAD files to a broader audience (Autodesk Inventor Publisher, Dassault Systemes’ 3D VIA Composer, and PTC’s Creo Illustrate, to name but a few examples). Some developers that don’t have CAD packages or have very little to do with engineering are also staking out territories in the same market. QuadriSpace, for example, recently launched an aggressively priced software, Share3D PDF. (At $199, it even undercuts the price of Adobe’s PDF publisher Acrobat X Standard, which costs $299.) Corel, better know among illustrators and graphics artists than manufacturers, keeps a foothold with Corel Designer Technical Suite. ACD Systems, a company better known for photo editing and illustration than mechanical design, takes on the market with Canvas software. Nearly all of them tout DWG support, the hallmark of design and engineering software.

“Getting technical illustrators to give up the pencil has been harder than getting designers to give up the drawing board,” Barnes reflected.

Since the technical illustration business—as the emerging 2D/3D publishing market is collectively called—is the intersection of designers, engineers, maintenance manual producers, and tech pub writers, the difference in their vocabularies is a frequent source of friction.

“Let’s say you’ve got a SolidWorks file, and you want to make a set of illustrations from it,” Barnes said. “The designer may have called [the file] a flange assembly. But when it gets down to the service document, you can’t call it a flange. You need to call it S37-95 replacement unit, or something like that. And that bill of materials [which identifies the specific part numbers] is often elsewhere [housed in PDM, PLM, or ERP, not CAD].”

Large Data Set, Lightweight Format

The purpose of CAD is to document a design in 3D with enough details and accuracy for subsequent manufacturing; therefore, the file tends to contain far more details than necessary for a technical illustrator. The challenge for software developers like Lattice is to offer users a way to repackaging CAD geometry so it’s suitable for reuse in technical illustrations.

“You have to understand what [the customer] wants to use the CAD data for,” observed Barnes. “If it’s for a part catalog, do you really need anything more than a good physical representation? In that case, maybe you can lighten [the imported file] by removing the internal details that don’t matter. On the other hand, if it’s to create a set of documents for outsourced manufacturing, then you can’t do that. You need to show assembly sequences and a certain level of details for people to interrogate. Obviously, that’s why we’re a bit fan of using lightweight data formats ... Our advice is always to keep the model as complete as you can, until you get to the publishing stage.”

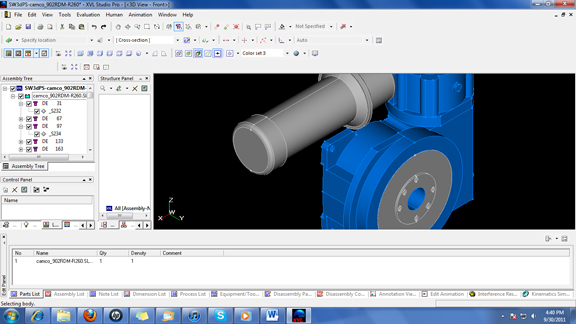

Lattice develops, updates, and licenses its lightweight data format XVL, originally developed by a group of mathematicians who felt VRML (Virtual Reality Markup Language) was still too heavy for their purpose. “We can typically get a CAD assembly’s size down to less than 1% of its original size,” said Barnes, “and it’ll still be accurate enough to do things like clash detection and design review ... We put a lot of work into our [XVL] format, in not only how small we can get the file size to be, but also in how quickly we can display it.” Lattice’s ability to handle large data sets, Barnes noted, is what distinguishes its technology from competition.

Mobile Push

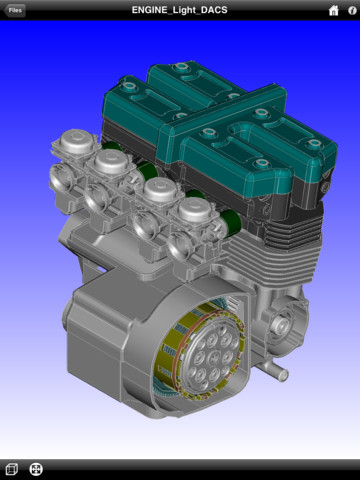

Among field service workers, maintenance crew, and repair technicians, lightweight tablets and smartphones are swiftly gaining ground as the preferred devices for accessing instructions and manuals. Faster boot time, instant-on WiFi, and touch-enabled screens make them easier to handle than netbooks and notebooks. In recognition of the new trend, Lattice recently launched iXVL View for the iPad, designed to let iPad users easily view XVL files published or created using Lattice XVL Studio.

The viewer, Barnes revealed, is just the first step in Lattice’s mobile strategy. The company envisions the viewer as an integrated part large manufacturers’ supply chain and ordering systems. It’s also working on a version of the viewer for Android devices.

“Five years ago, we were all about format. Our mantra was XVL, XVL, XVL—XVL everywhere, XVL on every desktop,” recalled Barnes. “Now, what I’ve noticed is the need to support multiple consumption devices A tablet or handheld device, a touch screen on the shop floor, a notebook with a PDF reader—as a vendor, we need to make sure we can support all those.”

Barnes has noticed that engineering data consumers (field technicians, for example) do not care about the format. Their satisfaction—or dissatisfaction—depends on whether they can view the data on their beloved hardware, whether it is an iPad, an Android phone, or a notebook PC.

“I don’t know how close we are to an airplane technician calling up an engine assembly from an iPad app, but I’m sure it’s not that far away,” said Barnes.

It was closer than Barnes thought. On August 28, a week after Barnes spoke these words, United Airlines gave 11,000 of its pilots iPads, replacing their clunky paper flight manuals with interactive data that’s always updated.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at kennethwong@digitaleng.news or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DERelated Topics